C&O Historical Society

Come all ye jolly lumbermen, and listen to my song

But do not get discouraged, the length it is not long;

Concerning of some lumbermen, who did agree to go

To spend one pleasant winter up in Canada-I-O.

It happened late one season in the fall of fifty-three

A preacher of the gospel one morning came to me;

Says he, “My jolly fellow, how would you like to go

To spend one pleasant winter up in Canada-I-O?”

To him I quickly made reply, and unto him did say,

“In going out to Canada depends upon the pay.

If you will pay good wages, my passage to and fro,

I think I’ll go along with you to Canada-I-O.”

“Yes, we will pay good wages, and will pay your wages out,

Provided you sign papers that you will stay the route;

But if you do get homesick and swear that home you’ll go

We never can your passage pay from Canada-I-O.”

“And if you get dissatisfied and do not wish to stay,

We do not wish to bind you, no, not one single day,

You just refund the money we had to pay, you know,

Then you can leave that bonny place called Canada-I-O.

It was by his gift of flattery he enlisted quite a train,

Some twenty-five or thirty, both well and able men;

We had a pleasant journey o’er the road we had to go,

Till we landed at Three Rivers, up in Canada-I-O.

But there our joys were ended, and our sorrows did begin,

Fields, Phillips and Norcross they then came marching in.

They sent us all directions, some where I do not know,

Among those jabbering Frenchmen up in Canada-I-O.

After we had suffered there some eight or ten long weeks,

We arrived at headquarters, up among the lakes;

We thought we’d find a paradise, at least they told us so,

God grant there may be no worse hell than Canada-I-O.

To describe what we have suffered is past the art of man;

But to give a fair description I will do the best I can:

Our food the dogs would snarl at, our beds were on the snow,

We suffered worse than murderers up in Canada-I-O.

Our hearts were made of iron and our souls were cased with steel,

The hardships of that winter could never make us yield;

Fields, Phillips and Norcross they found their match, I know

Among the boys that went from Maine to Canada-I-O.

But now our lumbering is over and we are returning home,

To greet our wives and sweethearts and never more to roam;

To greet our friends and neighbors; we’ll tell them not to go

To that forsaken G—- D— place called Canada-I-O.

I am indebted to the many friends who share my love of traditional songs and to the many scholars whose works are too many to include here. I am also incredibly grateful to the collector’s curators and collators of Wikipedia, Mudcat.org, MainlyNorfolk.info, and TheContemplator.com for their wise, thorough and informative contributions to the study of folk music.

I am indebted to the many friends who share my love of traditional songs and to the many scholars whose works are too many to include here. I am also incredibly grateful to the collector’s curators and collators of Wikipedia, Mudcat.org, MainlyNorfolk.info, and TheContemplator.com for their wise, thorough and informative contributions to the study of folk music.

I share this scholarly research on my site with humility, thanks, and gratitude. Please cite sources accordingly with your own research. If you have any research or sites you would like to share on this site, please post in the comment box.

Thanks!

| "Canada-I-O" | |

|---|---|

| Song | |

| Written | before 1700 |

| Songwriter(s) | Traditional |

"Canada-I-O" (also known as "Canadee-I-O" or "The Wearing of the Blue") is a traditional English folk ballad (Roud 309).[1] It is believed to have been written before 1839.[2]

When her love goes to sea, a lady dresses as a sailor and joins (his or another's) ship's crew. When she is discovered, (the crew/her lover) determine to drown her. The captain saves her and they marry.

Based on similarity of title, some connect this song with "Canaday-I-O, Michigan-I-O, Colley's Run I-O". There is no connection in plot, however, and any common lyrics are probably the result of cross-fertilization.

The Scottish song "Caledonia/Pretty Caledonia" is quite different in detail — so much so that it is separate from the "Canada-I-O" texts in the Roud Folk Song Index ("Canaday-I-O" is #309;[3] "Caledonia" is #5543). The plot, however, is too close for scholars to distinguish.

[ Roud 309 ; Ballad Index HHH162 ; Bodleian Roud 309 ; Wiltshire Roud 309 ; trad. arr. Nic Jones]

The ballad Canadee-I-O was printed in Leach, Folk Ballads & Songs of the Lower Labrador Coast.

Harry Upton of Balcombe, Sussex, sang Canadee-I-O to Peter Kennedy on September 5, 1963. This recording was included in 2012 on the Topic anthology of songs by Southern English singers, You Never Heard So Sweet (The Voice of the People Volume 21), and the song was included in 1970 in Ken Stubb’s book of English folk songs from the Home Counties, The Life of a Man. Another recording made by Mike Yates in 1974 was included in 1975 on the Topic collection of traditional songs from Sussex, Sussex Harvest, and in 2001 on the Musical Traditions anthology of songs from the Mike Yates Collection, Up in the North and Down in the South. Mike Yates commented in the latter’s booklet:

Canadee-I-O is something of a hybrid folksong, combining, as it does, two separate motifs; namely the girl who follows her truelove abroad, and the myth of the shipboard Jonah. As in many broadsides, however, there is a happy ending.

According to Frank Kidson, Canadee-I-O is a song which first appeared during the 18th century. In form, it is related to the Scots song Caledonia—versions of which were collected by Gavin Greig—although exactly which song came first is one of those ‘chicken and egg’ questions that so frequently beset folkmusic studies.

Harry Upton recalled singing this song in a Balcombe pub in 1940, and remained puzzled as to how a visiting Canadian soldier could join in a song which he believed to be known only to himself and his father. It could be argued that the Canadian might have more reasonably asked the question, since Harry is the sole English singer named among Roud’s 28 instances of the song.

Canadee-I-O is arguably Nic Jones’ best known song, recorded in 1980 for his Topic album Penguin Eggs. Bob Dylan recorded it also for his 1992 album,Good as I Been to You, John Wesley Harding for his Nic Jones tribute album, Trad Arr Jones, and Éilís Kennedy recorded Canadee-I-O in 2001 for on her debut CD Time to Sail.

Hannah Sanders sang Canadee-I-O in 2013 on her EP Warning Bells. She commented in her liner notes:

A beautiful traditional ballad, about a cross dressing sailor gal. This is how all good stories should begin! I doff my cap to Nic Jones’s version here.

Andy Turner sang Canadee-I-O as the September 6, 2014 entry of his project A Folk Song a Week.

The Outside Track sang Canadee-I-O in 2015 on their CD Light Up the Dark. They commented in their liner notes:

No album from a band with this many x-chromosomes in it would be complete without a story about a feisty girl on a mission. Nor only does she avoid walking the plank, but she arrives at her destination triumphant, ascending from stowaway to Captain’s Wife! One of the rarer cases where the song doesn’t end in death and destruction!

Matt Quinn learned Canadee-I-O from the singing of Harry Upton and recorded it for his 2017 CD The Brighton Line. He commented:

A girl escapes being thrown overboard by the ship’s crew when the captain falls in love with her. Well that’s one way to thwart death… Harry sang this to Mike Yates in the mid 1970s and he remains one of the [few] English traditional singers from whom it has been collected.

It’s of a fair and handsome girl, she’s all in her tender years:

She fell in love with a sailor boy, it’s true that she loved him well,

For to go off to sea with him like she did not know how,

She longed to see that seaport town called Canadee-I-O.

So she bargained with a young sailor boy, it’s all for a piece of gold.

Straightway then he led her all down into the hold,

Saying, “I’ll dress you up in sailor’s clothes, your jacket shall be blue,”

You’ll see that seaport town called Canadee-I-O.

Now when the other sailors heard the news, well they fell into a rage

And with all the whole ship’s company they were willing to engage,

Saying, “We’ll tie her hands and feet me boys, overboard we’ll throw her.

She’ll never see that seaport town called Canadee-I-O.”

Now when the captain he’s heard the news, well he too fell in a rage

And with all of his whole ship’s company he was willing to engage,

Saying, “She’ll stay all in sailor’s clothes, her collar shall be blue.

She’ll see that seaport town called Canadee-I-O.”

Now when they came down to Canada, scarcely ’bout half a year

She’s married this bold captain who called her his dear.

She’s dressed in silks and satins now, and she cuts a gallant show,

She’s the finest of the ladies down Canadee-I-O.

Come you fair and tender girls wheresoever you may be,

I’ll have you to follow your own true love, when he goes out on the sea.

For if the sailors prove false to you, well the captain he might prove true,

You see the honour that I have gained by the wearing of the blue.

It’s of a gallant lady, just in the prime of youth.

She dearly loved a sailor; in fact, she loved to wed,

And how to get to sea with him the way she did not know,

All for to see this pretty place called Canadee-I-O.

She bargained with a sailor all for a purse of gold,

And straightway he had taken her right down into the hold,

“I’ll dress you up in sailor suit; your colours shall be blue

And you soon will see that pretty place, called Canadee-I-O,”

When our mate had heard this, he fell into a rage,

Likewise our ship’s company was willing to engage:

“I’ll tie your hands and feet, my love, and overboard you’ll go,

And you’ll never see the pretty place called Canadee-I-O.”

And when the captain heard this: “This thing shall never be,

For if you drown that fair maid, hanged sure you’ll be;

I’ll take her to my cabin, her colours shall be blue,

And she soon will see that pretty place called Canadee-I-O.”

They had not arrived in Canada more than the space of half a year,

Before the Captain married her, and called her his very dear.

She can dress in silk or satin; she caught a gallant show;

She was one of the fairest ladies in Canadee-I-O.

Come all ye, young ladies, whoever you may be,

To be sure and follow your true love, if ever he goes to sea,

And if your mate, he do prove false, you’re captain he’ll prove true,

And you’ll see the honour I have gained by wearing of the blue

Thanks to Garry Gillard for transcribing Nic Jones’ lyrics.

Performances, Workshops, Resources & Recordings

The American Folk Experience is dedicated to collecting and curating the most enduring songs from our musical heritage. Every performance and workshop is a celebration and exploration of the timeless songs and stories that have shaped and formed the musical history of America. John Fitzsimmons has been singing and performing these gems of the past for the past forty years, and he brings a folksy warmth, humor and massive repertoire of songs to any occasion.

Festivals & Celebrations

Coffeehouses School

Assemblies

Library Presentations

Songwriting Workshops

Artist in Residence House

Concerts Pub Singing

Irish & Celtic

Performances

Poetry Readings

Campfires

Music Lessons

Senior Centers

Voiceovers & Recording

““Beneath the friendly charisma is the heart of a purist gently leading us from the songs of our lives to the timeless traditional songs he knows so well…”

“The Nobel Laureate of New England Pub Music…”

On the Green, in Concord, MA Every Thursday Night for over thirty years…

“A Song Singing, Word Slinging, Story Swapping, Ballad Mongering, Folksinger, Teacher, & Poet…”

Fitz’s Recordings

& Writings

Songs, poems, essays, reflections and ramblings of a folksinger, traveler, teacher, poet and thinker…

Download for free from the iTunes Bookstore

“A Master of Folk…”

Fitz’s now classic recording of original songs and poetry…

Download from the iTunes Music Store

“A Masterful weaver of song whose deep, resonant voice rivals the best of his genre…”

“2003: Best Children’s Music Recording of the Year…”

Fitz & The Salty Dawgs Amazing music, good times and good friends…

~Traditional

Stagolee was a bad man,

Ev'rybody knows.

Spent one hundred dollars

Just to buy him a suit of dothes.

He was a bad man

That mean old Stagolee

Stagolee shot BiUy de Lyons

What do you think about that?

Shot him down in cold blood

Because he stole his Stetson hat;

He was a bad ma@

That mean old Stagolee

Billy de Lyons said, Stagolee

Please don't take my life

I've got two little babes

And a darling, loving wife;

You are a bad man

You mean old Stagolee.

What do I care about your two little babes,

Your darling loving wife?,

You done stole my Stetson hat

I'm bound to take your life;

He was a bad man,

That mean old Stagolee.

The judge said, Stagolee,

What you doing in here?,

You done shot Mr. Billy de Lyons,

You going to die in the electric chair;

He was a bad man

That mean old Stagolee.

Twelve o'clock they killed him

Head reached up high

Last thing that poor boy said,

"My six-shooter never lied."

He was a bad man,

That mean old Stagolee.If you have any more information to share about this song or helpful links, please post as a comment.

Thanks for stopping by the site! ~John Fitz

I am indebted to the many friends who share my love of traditional songs and to the many scholars whose works are too many to include here. I am also incredibly grateful to the collector’s curators and collators of Wikipedia, Mudcat.org, MainlyNorfolk.info, and TheContemplator.com for their wise, thorough and informative contributions to the study of folk music.

I am indebted to the many friends who share my love of traditional songs and to the many scholars whose works are too many to include here. I am also incredibly grateful to the collector’s curators and collators of Wikipedia, Mudcat.org, MainlyNorfolk.info, and TheContemplator.com for their wise, thorough and informative contributions to the study of folk music.

I share this scholarly research on my site with humility, thanks, and gratitude. Please cite sources accordingly with your own research. If you have any research or sites you would like to share on this site, please post in the comment box.

Thanks!

| "Stack O' Lee Blues" | |

|---|---|

| Single by Waring's Pennsylvanians | |

| B-side | "Stavin' Change"[1] |

| Released | 1923 |

| Recorded | Camden, New Jersey, April 18, 1923 |

| Length | 3:21 |

| Label | Victor |

| Songwriter(s) | Ray Lopez (credited on single) |

"Stagger Lee" (Roud 4183), also known as "Stagolee" and other variants, is a popular American folk song about the murder of Billy Lyons by "Stag" Lee Shelton, in St. Louis, Missouri, on Christmas 1895. The song was first published in 1911 and first recorded in 1923, by Fred Waring's Pennsylvanians, titled "Stack O' Lee Blues". A version by Lloyd Price reached number one on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1959.

The historical Stagger Lee was Lee Shelton, an African-American pimp living in St. Louis, Missouri, in the late 19th century. He was nicknamed Stag Lee or Stack Lee, with a variety of explanations being given: he was given the nickname because he "went stag" (attended social events unaccompanied by a person of the opposite sex); he took the nickname from a well-known riverboat captain called Stack Lee; or, according to John and Alan Lomax, he took the name from a riverboat owned by the Lee family of Memphis called the Stack Lee, which was known for its on-board prostitution.[2] Shelton was well known locally as one of the Macks, a group of pimps who attracted attention through their flashy clothing and appearance.[3] In addition to those activities, he was the captain of a black Four Hundred Club, a social club with a dubious reputation.[4]

On Christmas night in 1895, Shelton and his acquaintance William "Billy" Lyons were drinking in the Bill Curtis Saloon. Lyons was also a member of St. Louis' underworld, and may have been a political and business rival to Shelton. Eventually, the two men got into a dispute, during which Lyons took Shelton's Stetson hat.[5] Subsequently, Shelton shot Lyons, recovered his hat, and left.[6] Lyons died of his injuries, and Shelton was charged, tried, and convicted of the murder in 1897. He was paroled in 1909, but returned to prison in 1911 for assault and robbery. He died incarcerated in 1912.[7]

The crime quickly entered into American folklore and became the subject of song, as well as folktales and toasts. The song's title comes from Shelton's nickname—Stag Lee or Stack Lee.[8] The name was quickly corrupted in the folk tradition. Early versions were called "Stack-a-Lee" and "Stacker Lee", while "Stagolee" and "Stagger Lee" also became common. Other recorded variants include "Stackerlee", "Stack O'Lee", "Stackolee", "Stackalee", "Stagerlee", and "Stagalee".[9]

A song called "Stack-a-Lee" was first mentioned in 1897, in the Kansas City Leavenworth Herald, as being performed by "Prof. Charlie Lee, the piano thumper".[10] The earliest versions were likely field hollers and other work songs performed by African-American laborers, and were well known along the lower Mississippi River by 1910. That year, musicologist John Lomax received a partial transcription of the song,[11] and in 1911, two versions were published in the Journal of American Folklore by the sociologist and historian Howard W. Odum.[12]

The song was first recorded by Waring's Pennsylvanians in 1923 and became a hit. Another version was recorded later that year by Frank Westphal & His Regal Novelty Orchestra, and Herb Wiedoeft and his band recorded the song in 1924.[13] Also in 1924, the first version with lyrics was recorded, as "Skeeg-a-Lee Blues", by Lovie Austin. Ma Rainey recorded "Stag O'Lee Blues", a different song based on the melody and words of "Frankie and Johnnie", the following year, with Louis Armstrong on cornet, and a version was recorded by Frank Hutchison on January 28, 1927, in New York, and is included in Harry Smith's famous Anthology of American Folk Music (Song 19 of 84).[10]

Before World War II, the song was commonly known as "Stack O'Lee". W.C. Handy wrote that it probably was a nickname for a tall person, comparing him to the tall smokestack of the famous steamboat Robert E. Lee.[14] By the time W.C. Handy wrote that explanation in 1926, "Stack O' Lee" was already familiar in United States popular culture, with recordings of the song made by pop singers of the day, such as Cliff Edwards.

The version by Mississippi John Hurt, recorded in 1928, is regarded by many as definitive.[10] In his version, as in all such pieces, there are many (sometimes anachronistic) variants on the lyrics. Several older versions give Billy's last name as "De Lyons" or "Delisle". Other notable pre-war versions were recorded by Duke Ellington (1927), Cab Calloway (1931), Woody Guthrie (1941),[10] and Sidney Bechet (1945).[15]

| "Stagger Lee" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single by Lloyd Price | ||||

| B-side | "You Need Love" | |||

| Released | November 1958 | |||

| Recorded | New York City, September 11, 1958 | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 2:20 | |||

| Label | ABC-Paramount | |||

| Songwriter(s) | Lloyd Price, Harold Logan (credited on single) | |||

| Producer(s) | Don Costa | |||

| Lloyd Price singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

Lloyd Price recorded an R&B rendition of the song as "Stagger Lee" in 1958, and it rose to the top of both the R&B and US pop charts in early 1959.[18] Although his version uses similar lyrics to previous versions of the song, his rendition features a different melody and has no lyrical refrain, making it shorter than previous recordings of the song. Price's version of the song was ranked number 456 on Rolling Stone's 500 Greatest Songs of All Time list, and also reached number 7 on the UK singles chart. Price also recorded a lyrically toned-down version of the song that changed the shooting to an argument between two friends for his appearance on Dick Clark's American Bandstand.[10]

| Chart (1959) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| UK Singles (The Official Charts Company)[19] | 7 |

| US Billboard Hot 100 | 1 |

| US Hot R&B Sides (Billboard)[20] | 1 |

| Chart (1958-2018) | Position |

|---|---|

| US Billboard Hot 100[21] | 260 |

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) Brown summarizes what little is known about the club as follows: "The Four Hundred Club was a 'social club,' but such clubs always had a moral front. (...) The Four Hundred Club may have been a type of black-and-tan club, catering to an interracial clientele, and as such would have been under pressure from reform policies." Brown cites a contemporary source from the newspaper St. Louis Star-Sayings, in which a member of the club states: "Mr. [Stack] Lee was our captain."

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) Based on the statements of witnesses, Cecil Brown retells the incident as follows: "Then Lyons grabbed Shelton's Stetson. When Shelton demanded it back, Lyons said no."

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link)

And in 1959, the New Orleans R&B singer and former Army serviceman Lloyd Price took one of those versions to #1....Instead, it's a total blast of a song, a spirited New Orleans rumble...

[ Roud 4183 ; Laws I15 ; Ballad Index LI15 ; trad.]

John Gibbon sang Stakolee in 1957 on his Topic album John Gibbon’s Disc.

Trevor Lucas sang Stagger Lee accompanied by guitar and mouth-organ in full early Dylan mode from the 1963 Folk Attick recordings in Sydney—plenty of suck and blow braced harmonica playing between the verses, and very typical of that protest folk singer period. This recording was included in 1994 on the Friends of Fairport cassette Together Again – The Attic Tracks Vol. 4.

Jesse Fuller sang Stackolee in a recording made by Peter Kennedy at Cecil Sharp House on March 19, 1965. This track was included in the same year on Fuller’s Topic album Move On Down the Line. Joe Boyd commented in the album’s sleeve notes:

Of all the hero or villain legends in American folk music, Stackolee ‘that bad man’ appears in both white and Negro ballads, often with references to the supernatural powers of his ‘Five Dollar Stetson Hat’. There was a notorious family named Lee in Memphis during the late nineteenth century, and a longshoreman (stevedore) was often known as a stacker. The song was part of Ma Rainey`s repertoire long before she recorded it in 1925. There are several recorded melodies for the song, of which I think Jesse’s is the most interesting.

Martin Simpson sang Stagolee in 2007 on his Topic album True Stories. He commented in his liner notes:

I first learned Stagolee from Mississippi John Hurt and recorded it when I was 17. The origins of the story were long guessed at, but it was widespread amongst blues singers, songsters, old timey musicians, R&B singers and rock and rollers throughout the 20th century. In 2003, Harvard University Press published Cecil Brown’s book, Stagolee shot Billy, a superbly written account of the facts. Lee Shelton shot Billy Lyons on Christmas Night, in 1859. I’ve attempted to put some of the facts back into the song without losing the poetry. Facts aren’t everything, but these are all true stories in one way or another.

Snakefarm sang Staggerlee in 2011 on their Fledg’ling CD My Halo at Half-Light.

See also the Mudcat Café thread Listen to different versions of Stagger Lee and Paul Slade’s essay A Christmas Killing: Stagger Lee.

Source: AmericanBluesScene.com

Today we’re bringing you another entry in American Blues Scene’s exclusive “Brief History of a Song” series.

The feud between Stagger Lee and Billy Lyons is as legendary as the one between the Hatfields and the McCoys; a truly American folk tale, retold countless times, about Stagger shooting Billy Lyons over, varyingly, a Stetson hat, a woman, a gambling debt, politics, or simply because Stagger was that mean of a man. Amazingly enough, the song may be the most re-recorded in history, with well over four hundred separate recordings to it’s name. A brief search of the Stagger Lee name could reveal recordings from Mississippi John Hurt, Furry Lewis, Lloyd Price, Professor Longhair, The Black Keys, Samuel L. Jackson, The Fabulous Thunderbirds, Wilson Picket, Taj Mahal, Fats Domino, Bob Dylan, Beck, Elvis Presley, Ike Turner, and a great many others.

Who was Stagger Lee, who goes by different names depending on the storyteller; Stagger, Stack-O-Lee, Stackalee, etc.? Was there a real Stagger Lee? Did he really run with Jesse James, have a magical Stetson, or take hell away from the devil when he died, as has been suggested?

The origins of this tale begin with a Christmas Eve bar fight in Saint Louis in 1895. The events of the murder were fairly commonplace; two friends, Billy Lyons and “Stagger” Lee Shelton, were drinking at Bill Curtis’s saloon and became enthralled in a conversation about politics. Billy grabbed Shelton’s hat in anger, and when he refused to return it, Shelton shot Billy in the gut, picked up his hat, and left. Lyons died from his wound shortly afterwards. That same night alone, five murders were committed in Saint Louis, but only one shot to world-wide infamy through a tangled web of politics, folklore, and raw persistence. The story was first covered in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat on December 28th, 1895. In 1896, the political scene was extremely tense, and with Saint Louis being one of the largest cities in the country, it was necessary for politicians to get every vote, including the black vote. This was increasingly relevant because the republicans were losing their stronghold, and because Shelton was a democratic organizer, and Lyons a Republican one, according to StaggerLee.com. The murder received significant exposure and political scrutiny, and resulted in a hung jury trial, after Stagger Lee had hired one of the most prominent lawyers in the state. Shelton’s case was retried in 1897, and Stagger Lee was found guilty of murder and sentenced to the notorious Jefferson penitentiary in Jefferson City, Missouri. It only took until 1902 or 1903, depending on the source, for the first printed lyrics referring to the Stagger Lee murder.

In 1909, then-Missouri governor Joseph Wingate Folk gave Shelton a full pardon on Thanksgiving day. By this time, folk versions of the Stagger Lee song were cropping up all across the South. The next year, legendary Library of Congress musicologist John Lomax received a partial transcription of what was called “The Ballad of Stagalee”, from a woman in Texas. She claimed that “this song is sung by the Negroes on the levee while they are loading and unloading the river freighters.” In 1911, Shelton broke into a man’s home, murdered him, and was sent to prison, but by 1912, Shelton received yet another pardon from another governor, apparently due to political pressure. Before he could be released, the infamous Stack-O-Lee died in prison of tuberculosis.

In the 1920s, a number of varieties of “Stagger Lee” began to be recorded. Ma Rainey and her band, (including a young Louis Armstrong on cornet), recorded Stack O’Lee Blues in 1925. Duke Ellington recorded a version in 1927, and in 1928 Mississippi John Hurt recorded what is perhaps the most famous and most definitive version of Stagger Lee’s song in history.

Police officer, how can it be?

You can ‘rest everybody but cruel Stack O’ Lee

That bad man, oh, cruel Stack O’ LeeBilly de Lyon told Stack O’ Lee, “Please don’t take my life,

I got two little babies, and a darlin’ lovin’ wife”

That bad man, oh, cruel Stack O’ Lee“What I care about you little babies, your darlin’ lovin’ wife?

You done stole my Stetson1 hat, I’m bound to take your life”

That bad man, cruel Stack O’ Lee…with the forty-four

When I spied Billy de Lyon, he was lyin’ down on the floor

That bad man, oh cruel Stack O’ Lee“Gentleman’s of the jury, what do you think of that?

Stack O’ Lee killed Billy de Lyon about a five-dollar Stetson hat”

That bad man, oh, cruel Stack O’ LeeAnd all they gathered, hands way up high,

at twelve o’clock they killed him, they’s all glad to see him die

That bad man, oh, cruel Stack O’ Lee

In 1931, folk great Woodie Guthrie sang a rendition of the song, likely adapted from John Hurt’s version, as the lyrics are very similar. During his field recordings, John Lomax often recorded the Stagger Lee song by various groups in the American South, from Texas to the Appalachia, often times in prisons. Some of these recordings can be found at the Library of Congress. Later, in 1941 and ’42, John’s son Alan recorded a number of versions during his own field recording trips for the Library of Congress. The song continued to capture the imaginations of singers and poets everywhere until 1958, when Lloyd Price released a version simply called “Stagger Lee”. The song exploded in popularity and became #1 on the Billboard Pop Charts. From there, dozens and eventually hundreds of recorded renditions of Stack’s story were spawned. In the 1960s, when Mississippi John Hurt was re-discovered, he would often play a folk-style story called “Stagolee” in which Stag and, interestingly enough, Jesse James, rob a card game in a coal mine. In 2007, Samuel L. Jackson played “Stack-O-Lee” in the movie Black Snake Moan, backed by Cedrick Burnside and Kenny Brown. Cedric is the grandson of legendary bluesman R.L. Burnside, who also sang popular versions of Stagger Lee’s song.

Stagger Lee has been sang about nearly countless times. His story has appeared in movies, poems, and even as it’s own comic book. Through every generation and nearly every musical style, Stagger Lee has made an appearance. Punk, Hawaiian, Heavy Metal, Disco, Rock, Blues, Folk, Bluegrass, Country, and Soul have all seen recorded versions, often with great popularity and by names as wildly famous as Elvis and the Isley Brothers. The story of bad Stagger Lee has continued to capture American’s, and then the world’s, imaginations for over 100 years.

To find a largely comprehensive documentation of 420+ “Stagger Lee” recordings, see StaggerLee.com

Performances, Workshops, Resources & Recordings

The American Folk Experience is dedicated to collecting and curating the most enduring songs from our musical heritage. Every performance and workshop is a celebration and exploration of the timeless songs and stories that have shaped and formed the musical history of America. John Fitzsimmons has been singing and performing these gems of the past for the past forty years, and he brings a folksy warmth, humor and massive repertoire of songs to any occasion.

Festivals & Celebrations

Coffeehouses

School Assemblies

Library Presentations

Songwriting Workshops

Artist in Residence

House Concerts

Pub Singing

Irish & Celtic Performances

Poetry Readings

Campfires

Music Lessons

Senior Centers

Voiceovers & Recording

““Beneath the friendly charisma is the heart of a purist gently leading us from the songs of our lives to the timeless traditional songs he knows so well…”

“The Nobel Laureate of New England Pub Music…”

On the Green, in Concord, MA Every Thursday Night for over thirty years…

“A Song Singing, Word Slinging, Story Swapping, Ballad Mongering, Folksinger, Teacher, & Poet…”

Fitz’s Recordings

& Writings

Songs, poems, essays, reflections and ramblings of a folksinger, traveler, teacher, poet and thinker…

Download for free from the iTunes Bookstore

“A Master of Folk…”

Fitz’s now classic recording of original songs and poetry…

Download from the iTunes Music Store

“A Masterful weaver of song whose deep, resonant voice rivals the best of his genre…”

“2003: Best Children’s Music Recording of the Year…”

Fitz & The Salty Dawgs Amazing music, good times and good friends…

John Henry was a li’l baby, uh-huh,

Sittin’ on his mama’s knee, oh, yeah,

Said: “De Big Bend Tunnel on de C & O road

Gonna cause de death of me,

Lawd, Lawd. Gonna cause de death of me.

John Henry, he had a woman,

Her name was Mary Magdalene,

She would go to de tunnel and sing for John,

Jes’ to hear John Henry’s hammer ring, Lawd, Lawd,

Jes’ to hear John Henry’s hammer ring.

John Henry had a li’l woman,

Her name was Lucy Ann,

John Henry took sick an’ had to go to bed,

Lucy Ann drove steel like a man,

Lawd, Lawd, Lucy Ann drove steel like a man.

Cap’n says to John Henry,

Gonna bring me a steam drill ’round,

Gonna take dat steam drill out on de job,

Gonna whop dat steel on down, Lawd, Lawd,

Gonna whop dat steel on down.

John Henry tol’ his cap’n,

Lightnin’ was in his eye;

Cap’n, bet yo’ las’ red cent on me,

Fo’ I’ll beat it to de bottom or I’ll die, Lawd, Lawd,

I’ll beat it to de bottom or I’ll die.”

Sun shine hot an’ burnin’,

Wer’n’t no breeze a-tall,

Sweat ran down like water down a hill,

Dat day John Henry let his hammer fall,

Lawd, Lawd, dat day John Henry let his hammer fall.

John Henry went to de tunnel,

An’ dey put him in de lead to drive,

De rock so tall an’ John Henry so small,

Dat he lied down his hammer an’ he cried,

Lawd, Lawd, dat he lied down his hammer an’ he cried.

John Henry started out on de right hand,

De steam drill started on de lef’—

“Before I ‘d let dis steam drill beat me down,

I’d hammer my fool self to death,

Lawd, Lawd, I’d hammer my fool self to death.”

White man tol’ John Henry,

“Nigger, damn yo’ soul,

You might beat dis steam an’ dr;ll of mine,

When de rocks in dis mountain turn to gol’,

Lawd, Lawd, when de rocks in dis mountain turn to gol`.

John Henry said to his shaker,

“Nigger, why don’ you sing?

I’m throwin’ twelve poun’s from my hips on down,

Jes’ listen to de col’ steel ring,

Lawd, Lawd, Jes’ listen to de col’ steel ring.”

Oh, de captain said to John Henry,

“I b’lieve this mountain’s sinkin’ in,

John Henry said to his captain, oh my!

“Ain’ nothin’ but my hammer suckin’ win’,

Lawd, Lawd, ain’ nothln’ but my hammer suckin’ win.”

John Henry tol’ his shaker,

Shaker, you better pray,

For if I miss dis six-foot steel,

Tomorrow’ll be yo’ buryin’ day,

Lawd, Lawd, tomorrow’ll be yo’ buryin’ day.”

John Henry tol’ his captain,

“Looka yonder what l see —

Yo’ drill’s done broke an’ yo’ hole’s done choke,

An’ you cain’ drive steel like me,

Lawd, Lawd, an’ you cain’ drive steel like me.”

De man dat invented de steam drill,

Thought he was mighty fine.

John Henry drove his fifteen feet,

An’ de steam drill only made nine,

Lawd, Lawd, an’ de steam drill only made nine.

De hammer dat John Henry swung’,

It weighed over nine pound ;

He broke a rib in his lef’-han’ side,

An’ his intrels fell on de groun’,

Lawd, Lawd, an’ his intrels fell on de groun’.

John Henry was hammerin’ on de mountain,

An’ his hammer was strikin’ fire,

He drove so hard till he broke his pore heart,

An’ he lied down his hammer an’ he died,

Lawd, Lawd, he lied down his hammer an’ he died.

All de womens in de wes’,

When dey heared of John Henry’s death,

Stood in de rain, flagged de eas’-boun’ train,

Goin’ where John Henry fell dead,

Lawd, Lawd, goin’ where John Henry fell dead.

John Henry’s lil mother,

She was all dressed in red,

She jumped in bed, covered up her head,

Said she didn’ know her son was dead,

Lawd, Lawd, didn’ know her son was dead.

John Henry had a pretty lil woman,

An’ de dress she wo’ was blue,

An’ de las’ wards she said to him:

“John Henry, I’ve been true to you,

Lawd, Lawd, John Henry I’ve been true to you.”

“Oh, who’s gonna shoe yo’ lil feetses,

An’ who’s gonna glub yo’ han’s,

An’ who`g gonna kiss yo’ rosy, rosy lips,

An’ who’s gonna be yo’ man,

Lawd, Lawd, an’ who’s gonna be yo’ man?”

Dey took John Henry to de graveyard,

An’ dey buried him in de san’,

An’ every locomotive come roarin’ by,

Says, “Dere lays a steel-drivin’ man,

Lawd, Lawd, dere lays a steel-drivin’ man.”

From American Ballads and Folk Songs, Lomax

I am indebted to the many friends who share my love of traditional songs and to the many scholars whose works are too many to include here. I am also incredibly grateful to the collector’s curators and collators of Wikipedia, Mudcat.org, MainlyNorfolk.info, and TheContemplator.com for their wise, thorough and informative contributions to the study of folk music.

I share this scholarly research on my site with humility, thanks, and gratitude. Please cite sources accordingly with your own research. If you have any research or sites you would like to share on this site, please post in the comment box.

Thanks!

John Henry | |

|---|---|

John Henry illustration by Roy E. LaGrone (1942) | |

| Born | 1840s or 1850s |

| Occupation | Railroad worker |

| Known for | American folk hero |

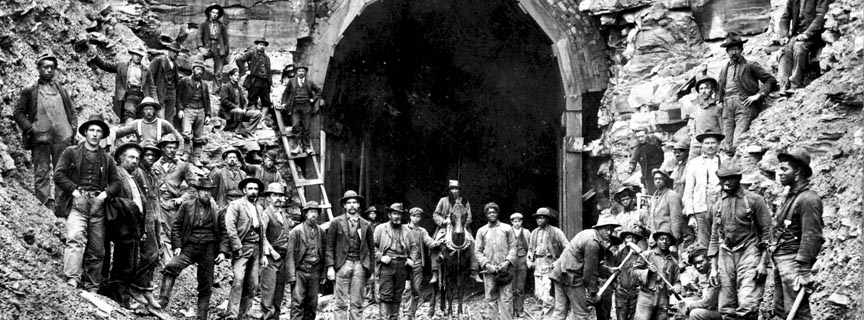

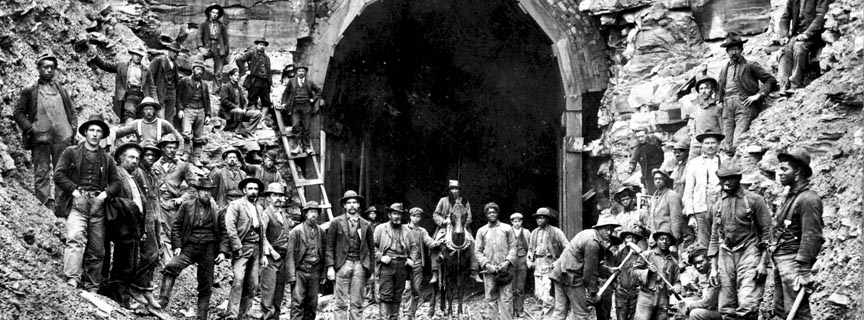

John Henry is an American folk hero. An African American freedman, he is said to have worked as a "steel-driving man"—a man tasked with hammering a steel drill into a rock to make holes for explosives to blast the rock in constructing a railroad tunnel.

The story of John Henry is told in a classic blues folk song about his duel against a drilling machine, which exists in many versions, and has been the subject of numerous stories, plays, books, and novels.[1][2]

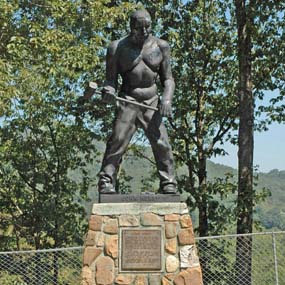

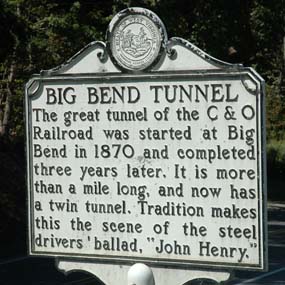

According to legend, John Henry's prowess as a steel driver was measured in a race against a steam-powered rock drill, a race that he won only to die in victory with a hammer in hand as his heart gave out from stress. Various locations, including Big Bend Tunnel in West Virginia,[3] Lewis Tunnel in Virginia, and Coosa Mountain Tunnel in Alabama, have been suggested as the site of the contest.

The contest involved John Henry as the hammerman working in partnership with a shaker, who would hold a chisel-like drill against mountain rock, while the hammerman struck a blow with a hammer. Then the shaker would begin rocking and rolling: wiggling and rotating the drill to optimize its bite. The steam drill machine could drill but it could not shake the chippings away, so its bit could not drill further and frequently broke down.

The historical accuracy of many of the aspects of the John Henry legend are subject to debate.[1][2] According to researcher Scott Reynolds Nelson, the actual John Henry was born in 1848 in New Jersey and died of silicosis, a complication of his workplace, and not due to proper exhaustion of work.[4]

Several locations have been put forth for the tunnel on which John Henry died.

Sociologist Guy B. Johnson investigated the legend of John Henry in the late 1920s. He concluded that John Henry might have worked on the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway's (C&O Railway) Big Bend Tunnel but that "one can make out a case either for or against" it.[5][3] That tunnel was built near Talcott, West Virginia, from 1870 to 1872 (according to Johnson's dating), and named for the big bend in the Greenbrier River nearby.

Some versions of the song refer to the location of John Henry's death as "The Big Bend Tunnel on the C. & O."[3] In 1927, Johnson visited the area and found one man who said he had seen it.

This man, known as Neal Miller, told me in plain words how he had come to the tunnel with his father at 17, how he carried water and drills for the steel drivers, how he saw John Henry every day, and, finally, all about the contest between John Henry and the steam drill.

"When the agent for the steam drill company brought the drill here," said Mr. Miller, "John Henry wanted to drive against it. He took a lot of pride in his work and he hated to see a machine take the work of men like him.

"Well, they decided to hold a test to get an idea of how practical the steam drill was. The test went on all day and part of the next day.

"John Henry won. He wouldn't rest enough, and he overdid. He took sick and died soon after that."

Mr. Miller described the steam drill in detail. I made a sketch of it and later when I looked up pictures of the early steam drills, I found his description correct. I asked people about Mr. Miller's reputation, and they all said, "If Neal Miller said anything happened, it happened."[6]

When Johnson contacted Chief Engineer C. W. Johns of the C&O Railroad regarding Big Bend Tunnel, Johns replied that "no steam drills were ever used in this tunnel." When asked about documentation from the period, Johns replied that "all such papers have been destroyed by fire."[5]

Talcott holds a yearly festival named for Henry, and a statue and memorial plaque have been placed in John Henry Historical Park at the eastern end of the tunnel.[7]

In the 2006 book Steel Drivin' Man: John Henry, the Untold Story of an American Legend, historian Scott Reynolds Nelson detailed his discovering documentation of a 19-year-old African-American man alternately referred to as John Henry, John W. Henry, or John William Henry in previously unexplored prison records of the Virginia Penitentiary. At the time, penitentiary inmates were hired out as laborers to various contractors, and this John Henry was notated as having headed the first group of prisoners to be assigned tunnel work. Nelson also discovered the C&O's tunneling records, which the company believed had been destroyed by fire. Henry, like many African Americans, might have come to Virginia to work on the clean-up of the battlefields after the American Civil War. Arrested and tried for burglary, John Henry was in the first group of convicts released by the warden to work as leased labor on the C&O Railway.[8]: 39

According to Nelson, objectionable conditions at the Virginia prison led the warden to believe that the prisoners, many of whom had been arrested on trivial charges, would be better clothed and fed if they were released as laborers to private contractors (he subsequently changed his mind about this and became an opponent of the convict labor system). In the C&O's tunneling records, Nelson found no evidence of a steam drill used in Big Bend Tunnel.[4]

The records Nelson found indicate that the contest took place 40 miles (64 km) away at the Lewis Tunnel, between Talcott and Millboro, Virginia, where prisoners did indeed work beside steam drills night and day.[9] Nelson also argues that the verses of the ballad about John Henry being buried near "the white house," "in the sand," somewhere that locomotives roar, mean that Henry's body was buried in a ditch behind the so-called white house of the Virginia State Penitentiary, which photos from that time indicate was painted white, and where numerous unmarked graves have been found.[10]

Prison records for John William Henry stopped in 1873, suggesting that he was kept on the record books until it was clear that he was not coming back and had died. Nelson stresses that John Henry would have been representative of the many hundreds of convict laborers who were killed in unknown circumstances tunneling through the mountains or who died shortly afterwards of silicosis from dust created by the drills and blasting.

The tale of John Henry has been used as a symbol in many cultural movements, including labor movements[11] and the Civil Rights Movement.[12] Philosopher Jeanette Bickell said of the John Henry legend:

John Henry is a symbol of physical strength and endurance, of exploited labor, of the dignity of a human being against the degradations of the machine age, and of racial pride and solidarity. During World War II his image was used in U.S. government propaganda as a symbol of social tolerance and diversity.[13]

Destination Freedom, a 1950s American old time radio series written by Richard Durham, featured John Henry in a July 1949 episode.[23]

The story of John Henry is traditionally told through two types of songs: ballads, commonly called "The Ballad of John Henry", and "hammer songs" (a type of work song), each with wide-ranging and varying lyrics.[2][24] Some songs, and some early folk historian research, conflate the songs about John Henry with those of John Hardy, a West Virginian outlaw.[24] Ballads about John Henry's life typically contain four major components: a premonition by John Henry as a child that steel-driving would lead to his death, the lead-up to and the results of the legendary race against the steam hammer, Henry's death and burial, and the reaction of his wife.[24]

The well-known narrative ballad of "John Henry" is usually sung in an upbeat tempo. Hammer songs associated with the "John Henry" ballad, however, are not. Sung more slowly and deliberately, often with a pulsating beat suggestive of swinging the hammer, these songs usually contain the lines "This old hammer killed John Henry / but it won't kill me." Nelson explains that:

... workers managed their labor by setting a "stint," or pace, for it. Men who violated the stint were shunned ... Here was a song that told you what happened to men who worked too fast: they died ugly deaths; their entrails fell on the ground. You sang the song slowly, you worked slowly, you guarded your life, or you died.[8]: 32

There is some controversy among scholars over which came first, the ballad or the hammer songs. Some scholars have suggested that the "John Henry" ballad grew out of the hammer songs, while others believe that the two were always entirely separate.

Songs featuring the story of John Henry have been recorded by many musical artists and bands of different ethnic backgrounds. These include:

The story also inspired the Aaron Copland's orchestral composition "John Henry" (1940, revised 1952), the 1994 chamber music piece Come Down Heavy by Evan Chambers and the 2009 chamber music piece Steel Hammer by the composer Julia Wolfe.[42][43]

They Might Be Giants named their fifth studio album after John Henry as an allusion to their usage of a full band on this album rather than the drum machine that they had employed previously.[44]

The American cowpunk band Nine Pound Hammer is named after the traditional description of the hammer John Henry wielded.

Bengalee singer-songwriter and musician Hemanga Biswas (1912–1987), considered as the Father of the Indian People's Theater Association Movement in Assam inspired by 'John Henry', the American ballad translated the song in Bengali as well as the Assamese language and also composed its music for which he was well recognized among the masses.[45][46] Bangladeshi mass singer Fakir Alamgir later covered Biswas' version of the song.[47][48]

In 1996, the US Postal Service issued a John Henry postage stamp. It was part of a set honoring American folk heroes that included Paul Bunyan, Pecos Bill and Casey at the Bat.[56]

Notes

{{cite AV media}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

Further reading

Mid-Late 19th Century John Henry, about whom little is known, is a subject of legend and song, and may well have been a real person living in the late 19th century in West Virginia or Alabama. The legend is the best-known black “tall tale,” honoring the achievements of an individual under difficult circumstances. In the case of John Henry, a “steel driving man,” he is memorialized for defeating a steam-powered machine in a test of strength and fortitude. As such, he continues to serve a vital mythic purpose in dramatizing the power of African Americans, and workers of all races.

Mid-Late 19th Century John Henry, about whom little is known, is a subject of legend and song, and may well have been a real person living in the late 19th century in West Virginia or Alabama. The legend is the best-known black “tall tale,” honoring the achievements of an individual under difficult circumstances. In the case of John Henry, a “steel driving man,” he is memorialized for defeating a steam-powered machine in a test of strength and fortitude. As such, he continues to serve a vital mythic purpose in dramatizing the power of African Americans, and workers of all races.

There is some evidence that John Henry was a historical man, probably an emancipated slave born in either North Carolina or Virginia in the decade of the 1840s or 1850s. He apparently grew to great size, perhaps over six feet tall and weighing over 200 pounds, matched by big appetites for food and hard work. Like many recently freed African Americans, he went to work for the railroads during the post-Civil War Reconstruction period. At the time, many rail lines were pushing west through the Appalachian Mountains, part of the drive to expand the still-young nation to the western frontier.

The challenge of penetrating those mountains was formidable. Tunnels had to be blasted through the rock using manual labor. The technique was to drive a deep hole into the rock with a steel shaft called a drill, in which explosives would be placed and ignited to blast incrementally into the mountain. The drill was pounded in by a “steel driver” wielding a sledgehammer of considerable weight. Each driver had an assistant, called a “turner,” who held the drill and rotated it between hammer blows. Both were hazardous, sweaty, exhausting jobs, but it was some of the only work available at that time. Newly designed mechanical drivers, powered by steam engines, were beginning to be tested and used to improve efficiency and reduce costs.

The historical John Henry is widely believed to have worked as a steel-driver for the Chesapeake & Ohio, or C&O Railway. Recent academic research suggests that the actual location may have been in Alabama in the year 1887. In any event, the C&O was at that time extending its line west into the Ohio Valley. Progress was halted at one point by Big Bend Mountain in Talcott, West Virginia, a one-and-a-half mile obstruction that could not be circumvented. Beginning in 1870, a tunnel was blasted through the mountain over a three-year period. A roadside sign near the tunnel entrance reads as follows: “Tradition makes this the scene of the steel drivers’ ballad, ‘John Henry’.” Hundreds of African American and white laborers died blasting this tunnel, and others like it, due to unsafe conditions and brutal 12-hour days. In such difficult and close quarters, songs and stories provided both entertainment and inspiration for the men.

The legend itself bears the hallmarks of mythic archetypal power. Usually told in the form of a ballad, it is one of the best-known and most recorded American songs. According to its narrative, the white railroad owners and their field bosses, or “Captains,” allowed the salesman for a steam engine driver to bring his machine to Big Bend Tunnel. John Henry, who in some versions of the tall tale was born eight feet tall and went to work at three weeks of age, realized this was an assault on his and his coworkers’ effectiveness and their livelihood. He, therefore, challenged the salesman to a contest between him and the machine. At the end of the day-long competition, John Henry had driven more steel with his 14-pound hammer than the mechanical contraption, but he died a martyr on the spot, exhausted by his Herculean efforts or perhaps from heartbreak on realizing what inevitably lay in store.

Beyond its powerful core of racial pride, the legend has migrated to more universal themes of workers and owners, underdogs and oppressors, the individual and society, and according to one commentator, even the Bill of Rights with its famous song lyric, “A man ain’t nothin’ but a man.” This may account for its ongoing vitality, and the countless versions of song and story that have proliferated over more than a century. Other American tall tales, including Paul Bunyan, Pecos Bill, and Johnny Appleseed, tell similar stories of individuals displaying superhuman power, and were part of America’s evolving self-narrative: conquering a hostile wilderness through individual drive, courage, and determination. As the lyrics to an early version of the ballad put it:

John Henry said to his captain:

“A man ain’t nothin’ but a man,

And before I’ll let your steam drill beat me down,

I’ll die with my hammer in my hand.”

The John Henry ballads probably originated as work songs for steel-drivers and other rail workers in the 1870s, and became more generalized as chain gang, worker, and prison songs. In later incarnations, they became folk, blues, or protest vehicles for the likes of Leadbelly, Woody Guthrie, Johnny Cash, Harry Belafonte, and Dave Van Ronk. If the legend did indeed have a historical basis, it surely became exaggerated with the passage of time and reinterpretation, but its power and relevance remain strong to this day.

In addition to the musical version, the legendary John Henry has been depicted in sculpture, illustrations, books, and short films, and even served as the inspiration for a stage play, a ballet, and a postage stamp. These help ensure that his message will live, or as one early writer put it, John Henry “…didn’t really die… just stopped livin’ in his Mammy’s shack, and started livin’ in the hearts of men, forever and a day.”

C&O Historical Society Wherever you may find yourself in the New River Gorge, take the time to quietly listen. Intertwined with the sounds of nature; birdsong, flowing water, and wind through the trees you will most likely also hear the whistle of a train. The original Chesapeake and Ohio railroad company line was constructed, following the New River through the Gorge, between 1869 and 1872. This line is very active today with dozens of daily runs by CSX railway corporation coal and freight trains, and Amtrak’s Cardinal passenger line.  The coming of the railroad through New River Gorge and southern West Virginia was the key event in shaping the modern history of this region. It transformed an isolated and sparsely populated land of subsistence farmsteads into a booming area of company owned coal mining and logging towns that supplied the natural resources that were the base of our nation’s industrial revolution, and were melting pots for diverse groups of new peoples. The C&O railroad was built primarily by two groups of working men, thousands of African-Americans recently freed from enslavement, and recent Irish Catholic immigrants; both groups anxious to begin new lives for themselves and their families as American citizens. The construction of the Chesapeake and Ohio railroad from the Virginia border through the Appalachian Mountains of West Virginia to the Ohio River was a monumental undertaking. Working from both ends of the state the workers spent three years digging and grading the rail bed, hand drilling and blasting the tunnels, and building the bridges and laying the tracks. Using hand tools and explosives, with horses and mules helping with the heaviest loads, these men literally carved the pathway for the railroad through the rugged mountains by hand.  One of the greatest legends of world folklore was born from these workers and their enormous task; John Henry “The Steel Driving Man”. The John Henry of legend is more myth than man; a tragic, larger than life hero involved in an epic battle between man and machine, which was immortalized in a popular folk song the “Ballad of John Henry”. The song sings of a little boy born with a fateful vision of a “hammer in his hand”, who as a steel driver during the construction of the Great Bend Tunnel on the C&O railroad at Talcott, West Virginia takes a hammer in each hand crying “A man ain’t nothing but a man”, as he faces down a giant steam powered drilling machine with the promise “If I can’t beat this steam drill down I’ll die with this hammer in my hand!” John Henry was the working mans champion in a contest to defend the pride and livelihood of his co-workers as they faced the threat of competition from machines at their work. True to his boyhood vision, John Henry triumphs in a fierce race with the drilling machine, but he “dies with his hammer in his hand” from the exertion of his great feat of strength.  Historical research supports John Henry as a real person; one of thousands of African- American railroad workers, specifically a steel driver, half of a two man team specializing in the hand drilling of holes up to fourteen feet deep into solid rock for the setting of explosive charges. Steel drivers swung a nine pound hammer straight and strong, all day, everyday, pounding assorted lengths of steel drill bits held by their steady and trusting partners, called shakers, who placed and guided the drill bits , and after every strike of the hammer turned or “shook” the bits to remove the pulverized dust. Together these teams of perfectly choreographed industrial artists would with concentration and muscle lead the way, boring the mile long tunnel through Great Bend Mountain and onward along the pathway throughout the length of New River Gorge. Legend and history merged when to test the viability of purchasing steam powered drilling machines to replace the human drilling teams, the railroad staged a contest at the Great Bend Tunnel. Chosen for their skill and speed to compete against the machine, John Henry and his shaker (history does not record his name, although legend sometimes calls him “Little Bill”) faced off side by side with the steam drill and won, drilling farther and faster. Whatever version of the race you choose to believe, the result was the same. The construction of the Great Bend Tunnel and the entire C&O rail line was not a product of the modern machinery of the industrial age but the basic physical labor of thousands of now unknown workers in an everyday struggle to make a living for themselves and their families. Historians also believe that John Henry died at the Great Bend Tunnel, one of the estimated hundreds of workers dying in rock falls, malfunctioning explosions and “tunnel sickness(the excessive inhalation of dust), who now rest in unmarked graves at the tunnel entrance below the statue of John Henry, who still stands as their champion. John Henry was but one of the thousands of men whose strong backs, sweat, blood, and desire to build a new life for themselves and their families were the true foundation for the coming of the Chesapeake and Ohio railroad, the growth of our nation, and the whistle you still hear today. |

Performances, Workshops, Resources & Recordings

The American Folk Experience is dedicated to collecting and curating the most enduring songs from our musical heritage. Every performance and workshop is a celebration and exploration of the timeless songs and stories that have shaped and formed the musical history of America. John Fitzsimmons has been singing and performing these gems of the past for the past forty years, and he brings a folksy warmth, humor and massive repertoire of songs to any occasion.

Festivals & Celebrations

Coffeehouses

School Assemblies

Library Presentations

Songwriting Workshops

Artist in Residence

House Concerts

Pub Singing Irish & Celtic Performances

Poetry Readings

Campfires

Music Lessons

Senior Centers

Voiceovers & Recording

““Beneath the friendly charisma is the heart of a purist gently leading us from the songs of our lives to the timeless traditional songs he knows so well…”

“The Nobel Laureate of New England Pub Music…”

On the Green, in Concord, MA Every Thursday Night for over thirty years…

“A Song Singing, Word Slinging, Story Swapping, Ballad Mongering, Folksinger, Teacher, & Poet…”

Fitz’s Recordings

& Writings

Songs, poems, essays, reflections and ramblings of a folksinger, traveler, teacher, poet and thinker…

Download for free from the iTunes Bookstore

“A Master of Folk…”

Fitz’s now classic recording of original songs and poetry…

Download from the iTunes Music Store

“A Masterful weaver of song whose deep, resonant voice rivals the best of his genre…”

“2003: Best Children’s Music Recording of the Year…”

Fitz & The Salty Dawgs Amazing music, good times and good friends…

Child Ballad #78

Cold blows the wind to my true love,

And gently falls the rain.

I’ve never had but one true love,

And in green-wood he lies slain.

I’ll do as much for my true love,

As any young girl may,

I’ll sit and mourn all on his grave,

For twelve months and a day.

And when twelve months and a day was passed,

The ghost did rise and speak,

“why sittest thou all on my grave

And will no let me sleep?”

“Go fetch me water from the desert,

And blood from out the stone,

Go fetch me milk from a fair maid’s breast

That young man never has known.”

“My breast is cold as the clay,

My breath is earthly strong,

And if you kiss my cold clay lips,

Your days they won’t be long.”

“How oft on yonder grave, sweetheart,

Where we were want to walk,

The fairest flower that e’er I saw

Has withered to a stalk.”

“when will we meet again, sweetheart,

When will we meet again?”

“when the autumn leaves that fall from the trees

Are green and spring up again.”

If you have any more information to share about this song or helpful links, please post as a comment.

Thanks for stopping by the site!

~John Fitz

I am indebted to the many friends who share my love of traditional songs and to the many scholars whose works are too many to include here. I am also incredibly grateful to the collector’s curators and collators of Wikipedia, Mudcat.org, MainlyNorfolk.info, and TheContemplator.com for their wise, thorough and informative contributions to the study of folk music.

I am indebted to the many friends who share my love of traditional songs and to the many scholars whose works are too many to include here. I am also incredibly grateful to the collector’s curators and collators of Wikipedia, Mudcat.org, MainlyNorfolk.info, and TheContemplator.com for their wise, thorough and informative contributions to the study of folk music.

I share their research on my site with humility, thanks, and gratitude. Please cite their work accordingly with your own research. If you have any research or sites you would like to share on this site, please post in the comment box. Thanks!

"The Unquiet Grave" is an Irish / English folk song in which a young man's grief over the death of his true love is so deep that it disturbs her eternal sleep. It was collected in 1868 by Francis James Child as Child Ballad number 78.[1] One of the more common tunes used for the ballad is the same as that used for the English ballad "Dives and Lazarus" and the Irish pub favorite "Star of the County Down".

A man mourns his true love for "a twelve month and a day". At the end of that time, the dead woman complains that his weeping is keeping her from peaceful rest. He begs a kiss. She tells him it would kill him. When he persists, wanting to join her in death, she explains that once they are both dead their hearts will simply decay, so he should enjoy life while he has it.

The version noted by Cecil Sharp[2] ends with "When will we meet again? / When the autumn leaves that fall from the trees / Are green and spring up again."

Many verses in this ballad have parallels in other ballads: Bonny Bee Hom, Sweet William's Ghost and some variants of The Twa Brothers.[3]

The motif that excessive grief can disturb the dead is found also in German and Scandinavian ballads, as well as Greek and Roman traditions.[4]

In 1941 the "Journal of the English Folk Dance and Song Society" Vol 4 no 2 included a long essay by Ruth Harvey. She compares motifs from "The Unquiet Grave" with other European ballads, including "Es ging ein Knab spazieren (Der tote Freier)" from Germany, and "Faestemanden I Graven" from Denmark.[5] She writes: "It is only inevitable that a song which certainly goes back to pre-Christian traditions should have suffered modification during the centuries."[6]

The Danish ballad "Faestemanden I Graven" was made into a short film, "Aage og Else" (1983).[7] Though not recorded till the nineteenth century, “The Unquiet Grave,” as a folk work, may date to the same period as those two seventeenth-century ballads. On the Fresno State University website, Robert B Waltz compares "The Unquiet Grave" with an older carol, "There blows a cold wind today," in the Bodleian Library MS 7683 (dated ca. 1500), but adds: "I must say that I find this a stretch; the similarities are slight indeed."[8]

[ Roud 51 ; Child 78 ; Ballad Index C078 ; Bodleian Roud 51 ; Wiltshire Roud 51 ; trad.]A.L. Lloyd sang The Unquiet Grave in 1956 on his and Ewan MacColl’s Riverside album of Child ballads, The English and Scottish Popular Ballads Volume I. Editor Kenneth G. Goldstein wrote in the album’s booklet:

Aside from its exquisite poety and music, this ballad is notable for its exhibition of the universal popular belief that excessive grief on the part of mourners disturbes the peace of the dead.

It is possible that this is only a fragment of a once popular longer ballad. In the form we have it today, no text has been reported earlier than the 19thcentury. The ballad is little known in Scotland and is quite rare in America. It is still current in England, however.

The text and tune sung by A.L. Lloyd were collected by Cecil Sharp from William Spearing of Ile Bruers, Somerset, excepting the last two stanzas, which were from Mrs. William Ree of Hambridge, Somerset.

See Child (78), Volume II, p. 78ff; Coffin, p.82; Dean-Smith, p.113.

Shirley Collins recorded this ballad in 1959 for her second LP, False True Lovers, a second time for her Collector EP English Songs Vol. 1, and a third time in 1967 for her album The Power of the True Love Knot. She commented in the first album’s notes:

From Cecil Sharp’s English Folk Songs. This is one of the classic pieces of English folk song literature. From one point of view it is a feminine fantasy or a wish, perhaps for the death of a lover, perhaps for a way of arranging a night visit by the lover, perhaps for a way of showing how strong her love is, perhaps of a feeling of guilt. Certainly, it is a ghost story designed to delight the imagination of young women. Finally, it shows the survival of ancient and widely distributed primitive beliefs about the treatment of the dead.

The rowdy Irish wake is the only one example of the common folk custom of a gathering in which ceremonial banqueting and games were indulged in to show honour to the dead person. The shade was given a great send-off to the other world. Sometimes guns were fired to send him skittering away in fear. Sometimes a special door was cut in the side of the wall so that the coffin could be taken out by that route; and then this hole was walled up so that the ghost could not find his way back into the house again.

In Scotland and Ireland it was believed that excessive grief prevented the dead from resting; that the tears shed by the mourners pierced holes in the corpse. In Persia they held that the tears shed by humanity for their dead flowed into a river in which the souls floated and drowned. Similar beliefs were held by the Greeks and Romans, and from mediaeval times throughout Germany and Scandinavia.

Sharp says that in England a belief was current that if a girl was betrothed to a man, she was pledged to him if he died, and was bound to follow him to the spirit world unless she solved certain riddles, or performed certain tasks, such as fetching water from a desert, blood from a stone, milk from the breast of a virgin…

and in the The Power of the True Love Knot album notes:

This song is a tender and magical expression of an ancient community belief: a very proper belief that when the mourning of a lover’s death started to drain life from the living, love was being misused. Tears flowed into the Styx, and the river swelled and became impassable, so the dead come back and warn the quick. On this track and elsewhere I play an instrument made for me by John Bailey, which is a dulcimer with a five-string banjo neck.

The Ian Campbell Folk Group with Dave Swarbrick sang The Unquiet Grave in 1963 on their album This Is the Ian Campbell Folk Group. This track was included in 2005 on their anthology The Times They Are A-Changin’.

Alex Campbell sang The Unquiet Grave in 1966 on his album Yours Aye, Alex; this track was included in 1966 on his compilation CD Been on the Road So Long.

Hedy West sang an American version The Unquiet Grave in 1967 on her Topic album Ballads. Her (or A.L. Lloyd’s) sleeve notes commented:

There’s widespread and ancient belief that excessive grieving over the dead disturbs their rest. The Greeks and Romans thought so, and the idea is as common in the Far East as in Western Europe. In Ireland as in Rumania it was thought that inordinate tears would burn a hole in the corpse, and in several ballads the dead complain that they cannot sleep because the tears of the living have wet their winding sheet. This ballad, of a restless ghost who confronts and reproaches the mourner, is probably a fragment broken off some longer, more complicated narrative. Though it’s been relatively common in England till recent times, it seems very rare in America, and has turned up only in a scattered handful of versions from Newfoundland, Virginia and North Carolina (which is where the present version comes from, collected by the indefatigable Frank C. Brown).

Jon Raven sang The Unquiet Grave in 1968 on the Broadside album The Halliard : Jon Raven.

Dave & Toni Arthur sang this ballad as Cold Blows the Winter’s Wind in 1969 on their Topic album The Lark in the Morning. The sleeve notes commented:

The ballad, usually called The Unquiet Grave, concerns a person who feels bound to sit and mourn by his (sometimes, her) lover’s grave for a period of time. In nearly all versions, the corpse complains of being disturbed, illustrating the ancient belief that excessive grief interferes with the peace of the dead. In archaic folklore, a constant concern, when faced with a death, is to try to ensure that the corpse makes a pleasant and reassured transit from the land of the living to the world of the dead. Otherwise the dead may return, uneasy and vengeful, to plague the living. Hence for instance the jollification at Irish wakes, intended to cheer and embolden the dead. Singers have ended our ballad in various ways, sometimes heartbroken and disconsolate, sometimes more or less lightheartedly as: “But since I have lost my own true love, I must get another in time.” Our tune is from Fred Hamer’s collection Garners Gay. The words are from Alfred Williams’s Folk-Songs of the Upper Thames.

Frankie Armstrong sang The Unquiet Grave in 1971 on her Topic album Lovely on the Water. A.L. Lloyd commented in the sleeve notes:

A woman laments long over the grave of her sweetheart, till he speaks from the grave and reproaches her for disturbing his rest. Usually in the ballads the setting and the characters are named, but here we know neither the who nor the where, and the supernatural climate is further charged with mystery on that account. The tale is old, like the belief that too much grief disturbs the dead, though to this day, in Eastern Europe, some peasants believe that mourner’s tears make an unhealing burn if they chance to light on a corpse. In some versions the dead person threatens to tear the living one to pieces (the favourite revenge of ghosts!) unless absolute fidelity can be sworn to. But Frankie’s version is milder, more consolatory, as fits her gentle character. By and large, the tune she uses is one recorded by Vaughan Williams at Dilwyn, Herefordshire.

John Kirkpatrick and Sue Harris sang this ballad as Cold Blows the Wind in 1976 on their Topic LP Among the Many Attractions at the Show Will Be a Really High Class Band and John Kirkpatrick did it again in 2007 on his Fledg’ling CD Make No Bones. He commented in the latter album’s sleeve notes:

When I moved to Shropshire in 1973 and started looking at the local folk music, the singing of May Bradley was a glorious revelation. I never saw her in the flesh, but Fred Hamer’s recordings of her in Ludlow during the 1960s proved to be a real treasure chest of wonderful songs wonderfully sung. She was the daughter of Ester Smith, a gypsy singer that Vaughan Williams had collected from in Herefordshire at the beginning of the century, and had some of her mother’s songs as well as plenty of others. This is her tune for what is sometimes known as The Unquiet Grave—Child Ballad no. 78. I’ve sung this before in a past life, but in revisiting the song I have added a few lines from other versions to fill out the sense of the words.

Two books of the songs Fred Hamer collected were published by EFDS Publications Ltd., and you can see this in the first one from 1967, Garners Gay. Or a much better option is to hear [May Bradley] singing it herself on the EFDSS LP Garners Gay issued in 1971, EFDSS LP 1006.

May Bradley’s version can also be found on her Musical Traditions anthology Sweet Swansea (2010).

Jo Freya sang The Unquiet Grave in 1992 on her CD Traditional Songs of England.

Sandra Kerr sang The Unquiet Grave in 1970 on the Argo Voices anthology series, Second Book, Record One (Argo DA96). Her daughter Nancy sang it in 1993 on the CD Eliza Carthy & Nancy Kerr. She referred in her sleeve notes to Evelin Wells’ The Ballad Tree, and to her mother singing this version onVoices.

Louis Killen learnt The Unquiet Grave from Brian Ballinger and sang in on his 1993 CD A Bonny Bunch.

Steeleye Span sang One True Love in 1998 on their CD Horkstow Grange, and they recorded The Unquiet Grave in 2009 for their CD Cogs Wheels and Lovers. Tim Harries commented in the former album’s notes:

The sources for [One True Love] are The Unquiet Grave, (spooky old English song), Lovely Joan, and a small fragment of Lowlands of Holland. The inspiration came largely from Borrowed Time by Paul Monette, a book you may be familiar with.

Kate Rusby couldn’t let the dead sleep on her 1999 CD Sleepless.

Like John Kirkpatrick, Jon Boden learned Cold Blows the Wind from the singing of May Bradley. He sang it with Bellowhead in 2010 on their CD Hedonism, and he sang it unaccompanied as the December 29, 2010 entry of his project A Folk Song a Day.

Rachel Newton sang The Unquiet Grave on The Furrow Collective’s 2015 EP Blow Out the Moon. She commented in the album’s notes:

I took the words for the well known ballad The Unquiet Grave from Child no. 78a; and the melody I use is based on a version I learned from the singing of Shirley Collins.

Siobhan Miller sang The Unquiet Grave on her 2017 album Strata.

| A.L. Lloyd sings The Unquiet Grave | |

|---|---|

| “Cold blows the wind to my true love, And gentle drops the rain, I never had but one true love And in Greenwood she is lain. |

|

| “I’ll do as much for my true love As any young man may, I’ll sit and weep all on her grave For a twelve month and a day.” |

|

| When the twelve month and one day was o’er, Her ghost begun for to speak, “Why sit you here all on my grave And will not let me sleep?” |

|

| “There’s one thing more I want, sweetheart, And one thing more I crave, And that’s a kiss from your lily-white lips And then I’ll go from your grave.” |

|

| “My lips are cold as clay, sweetheart, My breath smells heavy and strong, And if you kiss my lily-white lips, Your time would not be long.” |

|

| Shirley Collins sings The Unquiet Grave | Nancy Kerr sings The Unquiet Grave |

| “Cold blows the wind tonight, true love, Cold are the drops of rain, I only had but one true love And in Greenwood he lies slain. |

“The wind doth blow today, my love, And a few small drops of rain; I never had but one true love And in Greenwood he is lain. |

| “I’ll do as much for my true love As any young girl may, I’ll sit and mourn all by his grave For a twelve-month and a day.” |

“I’ll do as much for my true love As any young girl may, I’ll sit and mourn all on his grave For twelve months and a day.” |

| Now the twelve-month and a day being gone, The ghost began to greet: “Your salten tears they trickle down They wet my winding sheet.” |

The twelve months and a day being done, The dead began to speak: “Oh, who sits weeping on my grave And will not let me sleep?” |

| “It’s I, my love, sits by your grave And will not let you sleep. For I crave one kiss from your clay-cold lips And that is all I seek.” |

“’Tis I, your love sits on your grave And will not let you sleep. For I crave one kiss of your clay-cold lips And that is all I seek.” |

| “But lily, lily are my lips, My breath comes earthy strong. If you have one kiss from my clay-cold lips, Your time will not be long.” |

“Your breath is as the roses sweet, Mine as the sulphur strong. And if you get one kiss from my lips, Your time will not be long.“ |

| “’Twas down in yonder garden green, Love, where we used to walk. And the fairest flower that e’er was seen Has withered to the stalk.” |