I

The dull staccato throb in light rain on a dark night. Unseen barges make their way up the QianTian River—concrete shores marked by the arch of the bridge, the spans of beam stretched on beam, the impeccable symmetry of the street-lights broken by a stream of impatient headlights—the bursting aorta of commerce and hope that is Hangzhou.

The dull staccato throb in light rain on a dark night. Unseen barges make their way up the QianTian River—concrete shores marked by the arch of the bridge, the spans of beam stretched on beam, the impeccable symmetry of the street-lights broken by a stream of impatient headlights—the bursting aorta of commerce and hope that is Hangzhou.

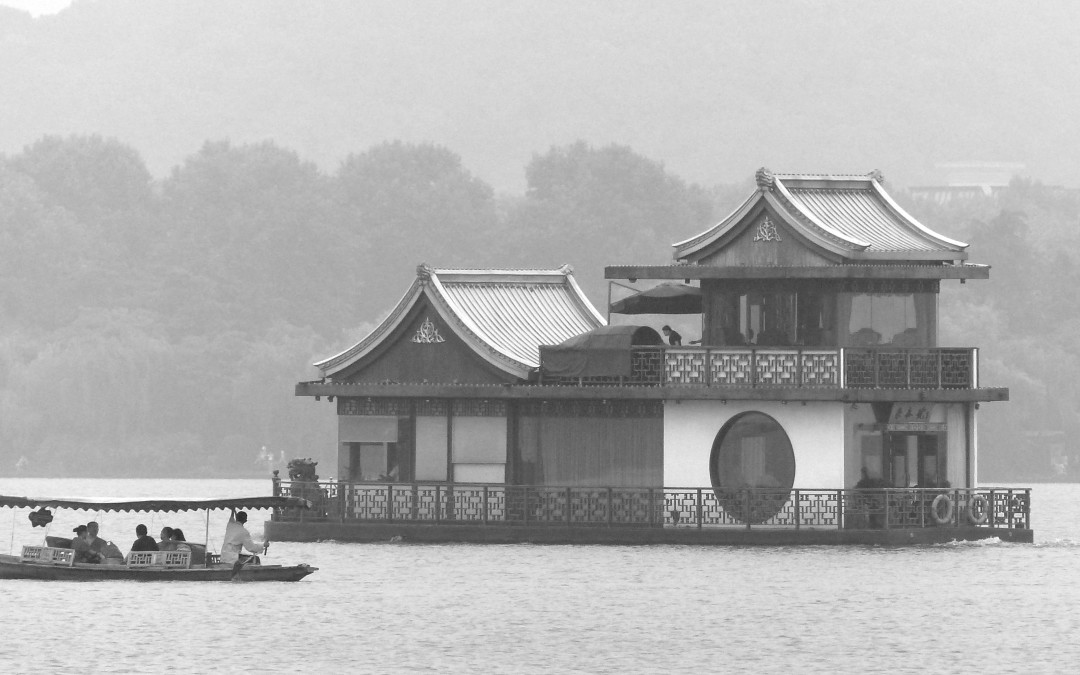

Or is it the torrent of humanity flowing east and west and north and south around the antiquities of West Lake? Lovers. Couples in every configuration and every intent. Families dragging or being dragged. Packs of friends so hip and cool and daring. So much unlike the China I remember. Soft wool coats: blue or gray. Mao buttons and short-visor caps. I fall just as easily into reverie as anticipation.

The grey fog and swirl of mist on West Lake outlines the rowing prams and party boats decked in imitation of palaces lost to time. On a far hillside—a bare shape of a gray palace on a gray background. Somewhere within: the lusty cries and plaintive words of crazy Li Po, drunk again and strewing words with a practiced and meticulous abandon—picked up by stooped bodies and weathered visages carried and thrown with feral joy—skipping stones stretched across still waters. Heavy, fluttering weight borne down by inescapable gravity.

Right now I am happy to my bones and as lonely and weak as a man can be. I scroll through pictures of my family and share them with the sky which seems heavy enough to fall—the dirt and smoke and smell of progress. Each picture tugs at my heart. I am not built to be away from home—Tommy scales a rock wall. Emma plays her ukulele. Margaret her guitar. EJ fixes his VW. Charlie juggles a soccer ball. Kaleigh collects seashells and beach glass. Pipo washes enormous pans in the camp kitchen. Denise sits in the backyard—our blessed perfect backyard—holding a chicken. I cling to them as wildly as wild can be. I will dare anyone. Any time. It is not a test I need to prepare for.

The craziness is in the contrast: this city of millions and millions and millions sprouting steel and glass and brick in every configuration of a weedy architect’s dream. I should be happy to be here, but I long for the simplicity of my back porch. Morning coffee with Denise. Kids busy. Friends who call. A slow jog. A bulb that needs to be changed. Only a fool would argue with me.

Jet lag wakes me in the middle of the night. I read Joyce for an hour. Is my head Dadelus or Bloom? It is too easy to confuse work of the head with work. Real work. Whatever it is that I need sleep for? Dave and Rob are still asleep. Long in jealous sleep. Or maybe like me—eyes wide-awake, curious if the sun ever shines in this city? Maybe stuck in fogged memories brushed in Song Dynasty waterstrokes. Rounded bellies surrounded by calligraphy’d words. China is not a country that etched its history on cave walls. Everything flows and dies and recreates itself in an unending cycle of births measured in massive ticks of time. For me and Dave and Rob at least: three days of incessant rain, mist and curiosity; still, I am a silent claw scuttling across the floors of a silent sea.

Yet we laugh as much as men have always laughed at the vagaries of fate in this country which seems to have created the word. We are ecstatic with our luck to be here. We scrounge like beggars for coffee in the morning. We force ourselves into taxis like hobo’s stuffing rucksacks. We teach the new elite of China: sons and daughters of scion and opportunity. Kids only, and no different, as if God only has three or four molds to work with: here is your intense child; here is your dreamy child; here is the child hobbled by a dull mind nurtured in like-minded fanaticism by parents deluded by assumptions of perfection, and here is the kid of the world—the ever-real world—the everywhere world: give me love; give me hope; give me joy; give me space. Save me from yourselves.

We work alongside the young and restless who are torn by conviction and inclination. The young who are prey to vanity, pretence, boldness and unplumbable magnanimity in equal measure. We call them by English names chosen in blithe randomness: this sounds good—I like this name—this is easy to remember—many famous people are named Richard. I want to scream and say that we are not so lost that we can’t remember the tongue-twisters of our youth. It is as easy for us to say to say that one sly snake slid up the stake and the other sly snake slid down as Liu Guo Ping or Ren Qi Wei or Sun Zhu. I like your name. I want your name. Your real name. There is no other way to begin.

Just tell us your name! and maybe the BBC won’t report every day on the gulf between us, on what our misunderstandings are, or on how we need to understand history. We are all ignorant, damn it, in every way, yet we are transcendent in every moment—if given the chance. I don’t want to meet another ex-pat who has been here for three years—or five years—or ten years, for they have nothing to tell me but their story, and as perfect and real as that story may be, I will measure that story against their own ignorance—and then we are surprisingly equal. I need to know that the wisdom of my backyard is as expansive as any unboundaried world. If not, why seek peace? It is unattainable. We do not need travel to suffocate bigotry. We only need to love and accept one thing that is not ours and build from there.

The young teachers from the school where we are working, Arvin, Angie, Addie and Ray, walked us around West Lake tonight—a quartet of twenty-somethings that seems to be the pillars of the new China: modern, ancient, vulnerable, and impertable. Arvin, in almost manic ecstasy, tells story after story of the history, the meaning, and the reality of every turn of the path in spontaneous bursts of every language he knew. Angie and Addie and Ray recreate the meaning, but not the ecstasy, blessed and cursed as they are by the temperance of defined lives.

We feast in some palace by the shore. Table after table full of men doing small shots of incredibly strong liquor—standing like warriors around a magnificent table. Sometimes a table of their wives locked in the chatter of tradition. Sometimes a table like us: a few friends; a few guests, and toasts and laughs in a broken dance of broken language cobbled into some kind of understanding. It almost felt like defiance, a changing of the guard. Sit with your wives, dammit! Yet, I was jealous of their camaraderie of tradition. We men barely change.

We watched a Chinese opera performed on the waters, sitting in the pouring rain surrounded within a sea of flimsy blue poncho’s. I loved my poncho, for it made me as Chinese as the rest of the crowd—my blue tarp like their blue tarp. My Mao jacket and their mao cap. I almost wanted to gasp like the crowd at every cool shift of scenery—of tens of feathers running across the water top—of lovers floating on ancient barges never quite touching prows—of ominous risings and fallings of girded columns of steel rising out of the waters of West Lake. Instead I squinted like an engineer to figure out the mechanism of reality that made people gasp. I regret that this always been my fallback to keep me from the lure of wonderment. I wanted to be lost in amazement, yet I was only gifted by the delight of engagement and deconstruction—the lost twin of faith.

Tonight, like everything, did not end: it was truncated by everything that truncates. It is absurd that I am still awake. Wisdom and experience plead with me to let go of the night, but I can’t, because louder than wisdom of experience is the voice of Li Po. The poet’s guttural cry croaked infinatum. Not unlike the barges—some conveyance I don’t see— a sound, merely, in a gray night, but I feel the dull, throbbing, staccato notes—the predictable heartbeat of a diesel reassurance lurching into the strong, moiling, and unceasing flow of tomorrow.

A tomorrow that is already here.